Bradley: What it’s like boxing Pacquiao, and how he can beat Barrios

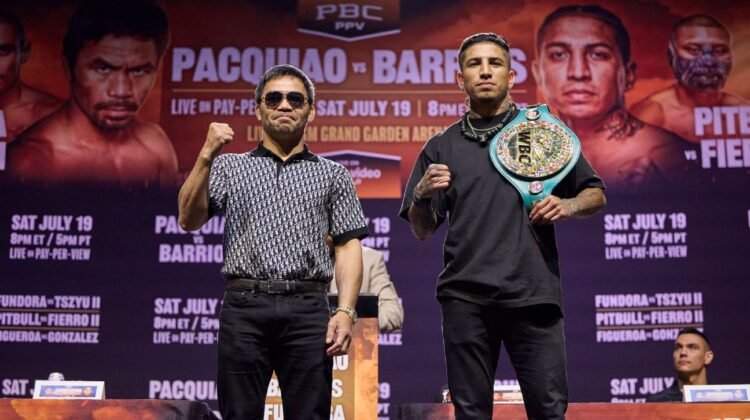

Manny Pacquiao is coming out of retirement at age 46, just a month after his induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. Boxing’s only eight-division world champion will return to the ring at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas on Saturday to face 30-year-old WBC welterweight champion Mario Barrios (Amazon Prime Video PPV, PPV.com, 8 p.m. ET).

This will not be an easy fight for Pacquiao after a long layoff. Barrios won the WBC interim title in September 2023, made one successful defense in May 2024 and was elevated to full champion ahead of his fight against Abel Ramos on November’s Jake Paul vs. Mike Tyson undercard. Barrios, a tall fighter for the division at 6-foot, was knocked down by Ramos in Round 6 of an entertaining fight. Despite the scare, Barrios eked out a 12-round split decision.

Yet, Barrios holds one of the most impressive résumés among today’s 147-pound champions. He owns a 2023 victory over Yordenis Ugas, who beat Pacquiao in August 2021, a loss that sent the Filipino legend into retirement. Barrios has also shared the ring with elite names such as Keith Thurman and Gervonta “Tank” Davis, both of whom handed him losses but provided him invaluable experience. Still, Barrios might be the weakest link among current welterweight champions, and that alone may explain Pacquiao’s motivation for his return. This return isn’t just about a paycheck; it’s about adding to his legacy.

In July 2019, Pacquiao became the oldest welterweight champion ever, at 40, by defeating Thurman in a performance that defied Father Time. Now he wants to surpass Bernard Hopkins, one of boxing’s all-time greats, as the oldest world champion in the sport’s history. Hopkins defeated Jean Pascal in 2011 at age 46 for the WBC light heavyweight title, then outdid himself at 48 by beating Tavoris Cloud for the IBF belt. The second-oldest champion was George Foreman, who reclaimed the heavyweight title at 45 by knocking out Michael Moorer in 1994.

But there’s a critical difference between what “Big George” did on his run, what Hopkins accomplished and what Pacquiao is attempting to do: Hopkins stayed active throughout his twilight years, and Foreman was active for 10 years during his return to the heavyweight crown. Pacquiao (62-8-39 KOs) has been out of the ring for over four years. There have been no tuneups, just a couple of exhibitions in 2022 and one in 2024. Jumping back into the fire with a hungry champion such as Barrios, who is naturally bigger, longer (with a 71-inch reach) and stronger, makes Pacquiao’s attempt alarming and historic.

What it feels like to face Pacquiao

I had the privilege of sharing the ring with Pacquiao on three occasions: 2012, 2014 and 2016. Each encounter brought a unique experience, driven by where he was in his career and where I was in mine. In 2012, Pacquiao was still at the height of his illustrious career. He hadn’t lost in seven years and had just come off a remarkable run, defeating some of the sport’s biggest names, icons such as Oscar De La Hoya, “Sugar” Shane Mosley, Miguel Cotto, Marco Antonio Barrera, Erik Morales and Antonio Margarito. Stepping into the ring with him for the first time, I imagined I was fighting a titan. Beyond the magnitude of the event, I found myself face to face with a charismatic and humble man whose soft-spoken voice and respectful demeanor draped over him like an invisible veil, contrasting to what stood across the ring from me on fight night.

The ring announcements felt shorter than in any other championship fight I’d had. My legs trembled uncontrollably as I bounced up and down to wake them. When I stopped bouncing, my legs would feel numb, as if they had been removed. Standing across from Pacquiao before the first bell rang, I could feel the weight of his presence. His aura was heavy, almost weakening me.

Pacquiao is, without question, the most outstanding athlete I’ve ever shared the ring with. Every movement he made was sharp, deliberate and unnervingly precise. His footwork and body feints kept me guessing and on edge, constantly tense, never knowing when his unorthodox combinations would deploy. His hand speed was deceptive and his sense of distance and his ability to change pace and rhythm made it all the more challenging.

What looked manageable in film studies felt overwhelming in real life. His first step into midrange came like lightning in an instant, and the moment he let his hands go, everything instantly became chaotic. I learned quickly that the crowd is his lifeline of energy. The more he gave it something to cheer about, the more ferocious he would become.

Pacquiao was far harder to hit than I had expected. His punching power was stunning; every connected shot sent a jolt through my head, and even the ones that missed sliced the air like bullets, whistling past my ears. When I did land something clean, he would clap his gloves together in defiance as if to say, “That all you got?” His stamina was unreal; his engine never stopped running. But what truly set him apart, though, was his tenacity and elite ring IQ. Try repeating a punch pattern twice, and you would find yourself eating a blazing fast counter from an unpredictable angle, his footwork in perfect sync with his hands, in short, explosive, choppy steps.

What made Pacquiao especially dangerous was his ability to sense when his opponent was fading. He could feel it, and that’s when he would turn up the heat. His strength was highly unusual for his size, at roughly 5-foot-6.

Let’s make this clear: Pacquiao’s B, C and D games are better than most fighters’ A game. Special fighters like him aren’t manufactured. They’re born. But 46 years of age is still 46.

How the fight could play out: Pacquiao’s athleticism vs. Barrios’ left hook

Expect Pacquiao to turn this fight into a battle from the opening bell. He’ll look to push the pace and close distance by disrupting Barrios’ rhythm with feints, head movement, throwing combinations and using his sharp footwork. In training videos, Pacquiao still flashes glimpses of his legendary hand speed and footwork. He’ll try to use that to explode forward with quick flurries and angle changes before Barrios can understand when to counter.

Pacquiao, the shorter man, knows he can’t stay at long range. That’s Barrios’ comfort zone, where he can use his long jab, straight rights, looping shots and hooks with full power. To nullify that, Pacquiao must close the gap and attack Barrios’ long torso. Those body shots are necessary to slow down Barrios’ legs, drain his stamina and reduce his snap, timing and will throughout the fight.

Being a southpaw gives Pacquiao a tactical edge. Barrios hasn’t faced many lefties in his career, and the last time he did, against Davis in 2021, he was peppered by left hands to the body and head and was ultimately stopped. I’m sure Pacquiao will try to mimic some of that success, using feints to mask his signature punch, the straight left hand, which he disguises with head movement and a step with his lead foot to the right, slipping outside and away from the peripheral vision of his opponent and firing straight down the middle with a sneaky left cross.

But this fight will not come without risks for Pacquiao. Once powered by his incredible athleticism, Pacquiao now will be left vulnerable by his explosive lunges and reaching. The older you get, the timing and balance don’t always line up perfectly. And Barrios’ counterpunching and game plan discipline will capitalize on those mistakes. He’s not the kind of fighter who overreacts like Pacquiao; he likes to wait, time his opponent and punch with intent at the perfect distance, taking care of offense and defense simultaneously.

Barrios will likely stay composed early, content to let Pacquiao initiate the pace and expend energy. He’ll start working behind a steady jab, using it to bust up Pacquiao’s face and disrupt his rhythm. He’ll pepper Pacquiao from the outside, and when Manny steps in with combinations, Barrios will look to time him with counters, particularly the straight right hand, a punch that has troubled the southpaw Pacquiao throughout his career.

Barrios’ left hook could be a sneaky game changer, especially to the body. Remember, Pacquiao has struggled with calf cramps throughout his career, and if Barrios invests in body work early, it could take the strength, steam and snap out of Pacquiao’s legs, eliminating his dynamic footwork and movement. As the fight gets deeper into the later rounds, Pacquiao’s pace and pressure might begin to slow. His early energy likely will fade, and Barrios will have opportunities to take over the action, remaining behind the jab and continuing to control distance. Once he believes Pacquiao is fading, he should attack him with counters that might hurt Pacquiao. Barrios is very disciplined in the ring. He fights smart, never letting the moment overwhelm him, and he’ll make small adjustments during the chaos Pacquiao loves to bring. He’ll show maturity by sticking to the game plan: manage distance and punish Pacquiao for his mistakes.

Pacquiao in decline? Let’s look at the numbers

As fighters age and fade from their physical prime, there’s often a noticeable decline, not just in activity levels but also in accuracy, reflexes and recovery. Older fighters might become more technical, taking fewer risks and relying on experience rather than volume or speed. But with that calculated caution comes reduced output and less physical ability to adapt under higher resistance.

In his fight against Ugas, Pacquiao didn’t just look a step behind, but he looked like he had aged overnight. Ugas’ composed counterpunching and sharp accuracy exposed the wear and tear of a long, restless career. Pacquiao’s legendary footwork and timing, once razor-sharp, seemed obsolete. Ugas’ reach, power, counterpunching and steady feet proved too much for the icon.

Ugas outlanded Pacquiao in total punches (151-130), jabs (50-42) and power punches (101-88). Ugas also connected on 59% of his power punches. For the first time, it became undeniable that Pacquiao had finally hit the wall that all great fighters eventually hit. Four years later, imagining any form of Pacquiao resurgence isn’t easy. Time hasn’t paused. Barrios is not only 16 years younger but also sharper and fresher. And he’s undoubtedly experienced.

Barrios possesses many traits that troubled Pacquiao against Ugas, such as steady footwork, acute timing, an excellent jab and the energy that comes with youth. Don’t let the video clips on social media fool you. Those Pacquiao shadowboxing sessions in parking lots, the blazing hand speed on the mitts or the thousands of crunches he grinds out look great. But looking great in the gym or against air doesn’t equate to being fight-ready under live fire after lengthy inactivity.

Remember how sharp Tyson looked on the pads before his exhibition with Paul? It’s one thing to look tremendous when no one’s hitting back. It’s an entirely different battle when your body begs for recovery, and it no longer comes as quickly. Reaction time slows and recovery stretches longer as we age. I know. Endurance, resilience and reflexes come naturally for the young. Yes, Pacquiao still has the heart of a warrior and will give whatever he has left in the tank, but Father Time is undefeated. Even his warrior spirit might not be enough to overcome this cherry-picked champion in the welterweight division.

Who wins?

This won’t be an easy fight for either Pacquiao or Barrios. Pacquiao will have his moments, maybe even rock Barrios with combinations, and his speed will win rounds. However, as the 12 rounds wear on and Pacquiao slows down, Barrios’ reach, sharp counters and grit will show that Pacquiao is beatable at this stage of his career. Ultimately, Barrios wins a hard-fought unanimous decision, not by domination but by being what he needs to be on this night. He will beat a legend, but one far out of his prime.