The predatory web of sextortion increasingly ensnares young athletes

Editor’s note: This story contains references to suicide and gun violence.

MARQUETTE, Mich. — The first message to Jordan DeMay’s Instagram arrived innocently enough.

“Hey,” it read.

It was the evening of March 24, 2022. The sender was “Dani.Robertts,” someone who would later assert to be a 19-year-old college woman from Atlanta. Her profile picture showed a pretty teen in a car with a German shepherd. She followed 1,805 accounts and had 683 followers, including one of Jordan’s teammates at Marquette High School, where he was a well-known football and basketball player.

Jordan DeMay, 17, stood 6-foot-2, with blond hair. He was the homecoming king, popular and funny, with an expansive group of friends. Injuries ended his goal of playing small-college football, but he was set to attend nearby Northern Michigan University with his girlfriend, Kyla, in the fall.

At 10:19 p.m., Jordan responded. “Who is you?” he asked.

The initial discussion between Jordan and Dani Robertts went on for nearly two hours, mostly involving small talk and some inconsequential picture exchanges — headshots mainly, another of Jordan in his basketball uniform. By then, Dani had won a measure of trust.

After midnight, Dani mentioned that she liked playing “sexy games.” She wanted to exchange more mature photos.

Jordan repeatedly mentioned that Dani might not be “real” or that this all might be “fake.” He jokingly responded to one request for a naked photo by sending a popular joke meme. It appears that, at times, he didn’t take any of this seriously.

Undeterred, Dani kept pressing and pressing, eventually sending an intimate photo of her own. Now it was Jordan’s turn, Dani said. He had something on her, after all. Fair is fair, Dani implied.

Jordan was in his bedroom, in the basement of the split-level home, in Michigan’s vast and desolate Upper Peninsula. It was after midnight. His father, stepmother and two young stepsisters were sleeping upstairs.

He went into his bathroom, pulled down his pants and snapped a photo in the mirror.

He hit send.

Almost instantaneously, the friendly Dani Robertts was gone. There had, of course, been no Dani Robertts.

All along, Jordan had been chatting with Samuel Ogoshi, then 22, in Lagos, Nigeria. Samuel was part of a small ring of online scammers, including his younger brother Samson, then 19, and a third man, Ezekiel Robert, then 19.

Once Jordan sent the photo, the three men sprang into action with a relentless, scripted extortion plan to harass and threaten him with public humiliation. Robert took over the chat while Samson Ogoshi scoured Jordan’s social media for friends, family, classmates, teachers and anyone else he could find. He quickly compiled a collage with Jordan’s intimate image surrounded by photos and social handles of people they could send it to.

“I have screenshot all ur followers and tags,” Robert wrote. “Can send this nudes to everyone and also send your nudes to your Family and friends Until it goes viral. All you’ve to do is to cooperate with me and I won’t expose you.”

Jordan didn’t respond. The direct messages kept coming.

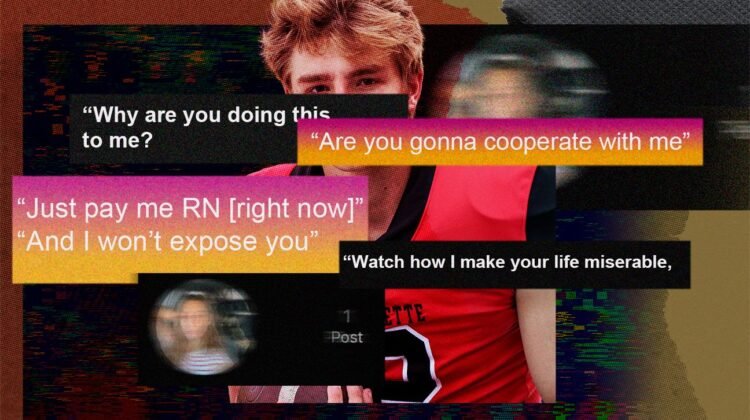

dani.robertts: “Are you gonna cooperate with me”

dani.robertts: “Just pay me RN [right now]”

dani.robertts: “And I won’t expose you”

Finally, Jordan wrote back: “How much”

dani.robertts: “$1000”

THE INGREDIENTS OF Jordan’s life — small-town athletic stardom, close-knit rural background, popularity and having a steady girlfriend — appear to have made him the perfect target for a new kind of crime, dubbed “financial sextortion” by the FBI.

Predators from thousands of miles away in Nigeria had zeroed in on Jordan as a source of easy money through internet blackmail. ESPN reviewed court records, police reports and previous news accounts to examine how loosely organized overseas criminal organizations entrap and extort American teens with terrifying, extreme and even deadly aggressiveness.

This predatory web has snared victims from all kinds of backgrounds. But growing numbers of young, male athletes are particularly vulnerable because of both their elevated social status locally and the desire to project a perfect image for potential college recruitment, according to Abbigail Beccaccio, the chief of the FBI’s Child Exploitation Operational Unit.

“If you look at our numbers and you look at how the bad actors are targeting victims, your school athletes are going to have a larger [online] footprint,” Beccaccio said. “It is going to make them more vulnerable to these types of targeted attacks. They have more to lose than another individual. … They’re looking at being scouted. They’re putting videos of their [highlights] out on social media.”

Since 2021, online sextortion has led to tens of thousands of cases and more than $65 million in losses, according to the FBI. More tragically, the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children reports, it has led to over three dozen suicides.

And that’s just the ones they know about.

Jordan DeMay was now in that kind of danger.

JORDAN RESPONDED THAT he didn’t have $1,000. He had $355, mostly earned from his job at McDonald’s. Clearly desperate, he tried to make a deal, sending $300 via Apple Pay. the scammers weren’t satisfied. They demanded $800 more and applied maximum pressure with repeated, increasingly threatening messages.

“Watch how I make your life miserable,” one read.

Jordan sent a screenshot of his finances to show he was nearly tapped out, then offered his final $55.

“No deal,” Robert, still posing as Dani Robertts, responded.

The scammers began to gloat at the power they held: “I love this,” Robert wrote before repeatedly starting countdowns to sending out the image. “10 … 9 … 8.”

“Why are you doing this to me?” Jordan asked.

“Because it’s going to be your worse night marrow [nightmare].”

On and on it went.

“I got all I need RN [right now] to make your life miserable dude.”

Jordan pleaded for relief. He appealed to decency.

“I am begging for own life,” he wrote.

The Nigerians never relented. Eventually they sent the collage, including Jordan’s picture, to Jordan’s girlfriend, Kyla Palomaki.

dani.robertts: “I bet your [girlfriend] will leave you for some other dude”

dani.robertts: “Just waiting for your [girlfriend] to get the text.”

dani.robertts: “You know what will happen.”

Kyla was asleep across town, unaware of it all. The Nigerians kept hammering away.

Jordan: “I will be dead. Like I want to KMS [kill myself]”

He again wrote he was out of money.

dani.robertts: “Okay, then I will watch you die a miserable death.”

Jordan: “It’s over, you win bro”

dani.robertts: “Okay”

dani.robertts: “Goodbye”

dani.robertts: “Enjoy your miserable life”

Jordan: “I’m kms rn [killing myself right now]”

Jordan: “bc of you”

dani.robertts: “good”

dani.robertts: “do that fast”

dani.robertts: “Or I’ll make you do it”

dani.robertts: “I swear to God”

At some point Jordan went upstairs to the kitchen and took a 40-caliber handgun, loaded with hollow-point bullets, out of an unlocked safe above the refrigerator. He returned downstairs, sat on his bed and typed out two texts.

One went to his girlfriend: “Kyla, I love you so much. I made a mistake and wish I could continue but I can’t do this anymore. This was a choice I made and I must pay myself.”

Eleven minutes later, he sent one to his mom, Jenn Buta, who lives nearby.

“Mother I love you.”

Moments later, he took his own life.

JOHN DEMAY SAID he heard a bang around 3:45 a.m. — about five hours after Jordan’s first contact with Dani. Due to the acoustics of the house and lacking any reason to think it might be gunfire, John later said he figured his son had just knocked something over downstairs. John was a former cop and avid hunter, well accustomed to the sound of gunfire. The noise didn’t register with him.

He has wrestled with the firearm being accessible but said someone determined to die by suicide will find a way.

Besides, he trusted Jordan implicitly. His son was about the happiest, most well-adjusted teen he knew. There had never been any mental health concerns or signs of depression. “The epitome of the cool kid,” Jordan’s stepmother, Jessica, said. The last John had seen of his son, Jordan was excitedly packing for an upcoming family vacation to Florida, a welcome respite from the snow and freeze of the long Lake Superior winter.

When silence followed the sound of the bang, John said he thought it was no big deal. He fell back to sleep.

Jenn Buta said she woke early at her home 7 miles away to find the message from her son.

They were exceptionally close, sharing a love of basketball and shopping and long talks on long drives, especially to Jordan’s travel tournaments. She would offer lessons on life and hoops — look people in the eye, hold the door, shoot the ball! Jordan, in turn, made her listen to his music — Drake, Post Malone, Fetty Wap.

They texted throughout the day, every day — even as he approached 18. About parties. About Kyla. About whatever. He had video called her the night before while shopping for suntan lotion and cold medication.

So being greeted by a text from her son a little before 7 a.m. was not surprising.

“I love you too,” she wrote back. “I hope you got a good night’s sleep.”

Except Jordan didn’t text back. Five minutes. Ten. Fifteen. This was unusual. She grew concerned.

“Call it a mother’s intuition, but I knew,” Buta said. “Something’s wrong.”

“Are you OK,” she wrote.

No response.

“Jordan?”

It was now almost 7:30 a.m. Jordan should be at school. She texted Kyla, asking if Jordan was there. Kyla wrote back that he wasn’t, and that he wasn’t responding to her texts either.

Buta tried to tell herself not to panic. She texted John asking if Jordan was somehow still at his house. This would be unusual. Jordan got out the door every morning. He was never late. He was self-sufficient.

John went immediately downstairs, whipped open Jordan’s door and flipped on the light. It was a scene no parent should ever see: his son, lifeless, still sitting up in bed, gun still in his right hand, his red iPhone nearby.

“You just knew immediately what happened,” John said. “It was obvious what happened. He’s got the pistol and the mess from the exit was on the wall.”

He stumbled back upstairs.

“I couldn’t even breathe,” John said. “My wife thought I was having a heart attack. I couldn’t even get it out. I just said: He shot himself.”

He called Buta. It was just nine minutes after she had texted about their son. She’d been staring at the phone, trying to will it to deliver some good news: an oversleep, a flat tire, anything.

John somehow blurted it out.

“He’s gone.”

JENN BUTA SAID she doesn’t remember much from the ensuing days. She paced back and forth in her house, unable to eat, unable to sleep. “I still don’t sleep,” she said.

The funeral was a massive affair, maybe 2,000 mourners, stuffed not just into the pews of Lake Superior Christian Church but watching on television in every office, hallway or available inch of the place. Others simply couldn’t get in. Cars stretched up and down State Highway 553. Friends choked out speeches. Tears were everywhere.

The crowd size was both stunning, yet unsurprising. Jordan was popular yet approachable and self-deprecating. “The All-American kid,” Jessica DeMay said. When he got his driver’s license, he proudly bought an old, red 1994 Dodge Ram with more than 200,000 miles on it.

“Crank windows, cassette tape,” his mother said with a laugh.

“Total rust bucket,” his father added.

He drove it around like it was a Bentley.

He cracked constant jokes. He impressed by not needing to impress, drew in friends by looking outward to help others, led through actions.

He was a well-known athlete across the Upper Peninsula. He had played everything, including on travel baseball and basketball teams that would scoop up talent from tiny, old lumber and mining towns before heading off to represent an often-forgotten region. It’s the bond of the UP; distance breeding togetherness.

Teammates and even rivals showed up at his funeral — often in their team jerseys — some coming from more than two hours away.

His athletic career had been marred by injuries, but it also sparked an interest in a real career — Jordan planned to study to become a physical therapist.

It felt like he was just starting life. Instead, he ended his.

LOWELL LARSON WAS then a detective, but now the undersheriff, for Marquette County. He had been one of the first to arrive at the DeMay home that morning.

“We knew that we had a suicide,” Larson said. “We didn’t know why he did it.”

Suicides are nearly always cloaked in confusion. They aren’t usually the result of crimes. Larson said he knew John DeMay from a lifetime of both living in Marquette — population just 21,000, but the biggest city for nearly 200 miles. He was pained by the tragedy. He said he didn’t think it would become an investigation though.

Jordan’s phone was passcode-locked (state police would later crack it by combining Jordan’s jersey numbers in football and basketball). Even if Larson had been able to gain access, Jordan had deleted the Instagram messages.

“I can’t just write a bunch of search warrants for every death investigation to get everybody’s social media for a fishing expedition,” Larson said. “We have to have probable cause that a crime has been committed.”

The first clue came later that day. A devastated Kyla drove with a friend to nearby Presque Isle Park. It’s where she and Jordan would go after hitting Dunkin’ for an iced coffee or a strawberry dragon fruit refresher. “We had so many conversations, just sitting on the rocks, watching the sun set,” Kyla said.

Now, she was trying to make sense of it all. “I was in a state of shock, but I just kept saying: There’s no way,” Kyla said.

Her phone buzzed with messages of condolence. Amid the flood, she opened Instagram and discovered a direct message from 3:38 a.m. It was from a name she didn’t know — Dani Robertts.

It contained the picture of Jordan.

“I immediately knew this was the reason,” Kyla said.

She went home and wrote the account back: “what is this about?”

To Kyla, this was a mystery. To the Nigerians on the other end, this was another potential opportunity.

Despite Jordan’s final “kms” messages, they didn’t yet know he was dead. They put together screenshots of all of Kyla’s family and began bullying Kyla, according to an exchange that Kyla provided to Bloomberg and confirmed with ESPN.

dani.robertts: “I swear I will ruin his life with this”

Kyla: “He killed himself last night. Please don’t”

dani.robertts: “Do you want me to ruin his life?”

Kyla: “He’s gone. No”

Dani: “Do you want me to ruin his life? Yes or no”

Kyla: “He’s already ruined. WDYM? [What do you mean?]”

Dani: “He [is] going to be in jail”

Kyla: “HE’S DEAD”

Dani: “And this will go viral”

Kyla: “HE SHOT HIMSELF”

dani.robertts: “Haha. Do you want me to end this. And delete the pics?”

dani.robertts: “Yes or no…”

dani.robertts: “Cooperate with me and this will end…”

dani.robertts: “Just do as I say and all this will end.”

Kyla went to her parents, although that wasn’t easy. “It is embarrassing,” Kyla said. “It’s like, ‘Dad, Jordan sent a naked photo to another girl.’ You don’t want your parents to think badly about your boyfriend, who I was still madly in love with, even though he just died. It was hard for me to even say.”

Word quickly got to Larson, who soon obtained an emergency order from a magistrate to compel Meta, the parent company of Instagram, to turn over records.

Meta sent over 700 pages, featuring conversations the scammers, posing as Dani Robertts, had conducted with over 100 accounts. Larson quickly realized the conversations were part of “a script” using similar language and grooming patterns.

“It was almost the exact same text,” Larson said. “It was clear they were doing the same thing over and over again. You find out what works, and you keep doing it.”

To Larson, this wasn’t a suicide. It was murder.

META PROVIDED IP ADDRESSES that allowed him to confirm he was dealing with criminals overseas. That was backed up when he obtained a warrant to search the local newspaper, The Mining Journal, for the IP addresses of anyone who had read Jordan’s obituary. He suspected that after Kyla told them Jordan was dead, they would have sought more information about it.

“I was trying to put myself in the mind of the criminal,” Larson said.

Four IP addresses came back from Nigeria. One of them matched with an address from the Dani Robertts account. The FBI would later travel to Nigeria where, with government help, agents found searches on the Ogoshi computer that included “Michigan suicide” and “Instagram blackmail death.”

Scammers have long used the internet to target potential victims, especially the elderly. In recent years, they have turned their attention to teenagers.

Concerns about organized sextortion began mounting in 2021, when both the FBI and the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, which monitors these crimes, began hearing the same terms — particularly “ruin your life” — being reported by victims via their tip line.

“These crimes had been sexually motivated,” Lauren Coffren of NCMEC said. “But this was different. Now they were financially motivated.”

The crime is popular, the FBI says, because of its ease and the fact that it is cheap to establish. Samuel Ogoshi, for example, made up the “Dani Robertts” account after paying another Nigerian $4.80 for some pictures of an actual girl from a hacked American account, according to court records.

“Our victims’ subset really began to shift,” said Beccaccio of the FBI. “Instead of having a high number of females targeted, our male population between the ages of 14 and 17 really started to get targeted. We also found that the suicide risk in that population was also much higher than that in our traditional sextortion.”

In 2022, NCMEC received 10,000 reports of such incidents. By 2024, it had risen to more than 30,000. But because victims are reluctant to report, law enforcers say the real numbers are probably much higher.

“We don’t know what we don’t know,” Coffren said. “And that is incredibly terrifying. There remains so much stigma and shame, especially around male victimization, which is why they are targeting young men.”

That underreporting includes potential suicides. Though NCMEC says at least 36 have occurred since 2021, the real number is unknown.

In this case, for example, if the scammers hadn’t contacted Kyla, there would have been no cause for a police investigation, and Jordan’s death likely would have been just another inexplicable suicide.

“This is a parent’s worst nightmare,” Coffren said. “There is nothing to look out for. A kid can go to bed in their bedroom, and you might not see them the next morning.”

THE KNOWN SUICIDES, though, are everywhere and continuing, each as heartbreaking as the next — an unrelenting crime wave in plain sight but with little attention.

James Woods, 17, a track sprinter from Streetsboro, Ohio, died in 2022 after sextortionists wrongly told him he would go to prison for sending a nude image. Carter Bremseth, 16, a golfer from Olivia, Minnesota, died in 2021. Riley Basford, 15, of Potsdam, New York, an avid outdoorsman who played lacrosse and football, died in 2021.

Eli Heacock, 16, of Barren County, Kentucky, a track and tennis athlete, took his own life last February. He had been pressured after extortionists used AI to turn a clothed picture into a nude before threatening to release it. Bradyn Bohn, 15, of Kronenwetter, Wisconsin, a baseball player, died by suicide last March. His final note included a line referring to his sextortionist: “Make sure he gets caught.”

“We’ve seen the chats,” Coffren said. “The societal pressure, the pressure these offenders are putting them under, the fear, the shame, the guilt, all of that combines in such a sense of urgency and rapidness. It is relentless. They are terrifying these kids into believing they have no recourse, they have no out. And the kids are believing it.”

Perhaps most concerning is the speed. All of the victims died within 24 hours of initial contact, most within hours, NCMEC reports.

In 2021, Braden Markus, 15, a football player at Olentangy High School in Ohio, for example, took his own life just 27 minutes after he was first contacted. It took 10 months for his parents to access his phone and discover why.

“There is no advanced warning,” John DeMay said. “Someone came into my house and murdered my son while we were sleeping.”

“This was pure torture,” Larson said. “They tortured him from 5,200 miles away.”

John DeMay and Jenn Buta say that since they’ve made Jordan’s story public, they have heard from hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people who have been victims of sextortion at some level.

“Just this week I had four reach out in a 24-hour period,” Buta said.

The parents’ advice for teens getting targeted is simple: Shut off the computer as soon as a questionable message pops up, walk away and then go tell a trusted adult. The criminals are looking for money, and if they think an avenue has dried up, they’ll likely move on. It’s like a fish wiggling off the hook. But if they believe a fish is still on the hook, there is no amount of appeasement — or payouts — that will stop them from pushing for more.

“If you don’t engage with them, they’re going to stop and move on,” John said.

Meanwhile, NCMEC suggests immediately reporting the account to a social media platform and reaching out to the organization’s hotline: 1-800-843-5678. Laws and policies can help keep the image off the internet.

“We can help,” Coffren said. “We can handle it.”

A slew of new state laws — often pushed into passage by victim families — have made sextortion a felony. Law enforcers say that since most of the international criminals don’t believe anyone will actually take their own life, they won’t actually face criminal consequences for what they believe is just a minor financial crime.

It’s why a message had to be sent.

MARK TOTTEN BECAME the U.S. attorney for the Western District of Michigan in May 2022. He said it was his second day on the job when he was briefed on financial sextortion. He had had a vague awareness of the concept but was stunned at the sophistication and callousness of the operation.

“You can see why this is attractive to fraudsters because this kind of scam only takes hours, sometimes not that long,” Totten said. “With a senior citizen, it can take weeks and months to build that kind of trust.”

He described Jordan’s case as the most important prosecution of his tenure. He left the post last January and is now running to be Michigan’s attorney general.

The key was not just finding the Ogoshis and Robert. It was charging them and extraditing them to the United States, which is rare.

“There was a real need to create a deterrent in Nigeria and everywhere overseas,” Totten said. “We needed to make it clear that this was a crime with real consequences … including imprisonment in the United States.”

The FBI’s Beccaccio described local Nigerian law enforcers as “nothing but cooperative with us.” It took over a year, but the Ogoshi brothers were brought to the United States in August 2023 where they soon pleaded guilty to conspiracy to sexually exploit a minor. Robert is still in Nigeria, fighting extradition. Five American men — one from Alabama and four from Georgia — pleaded guilty in April to having helped the scammers launder their extortion money.

On Sept. 5, 2024, in the U.S. District Court in Marquette, packed with Jordan’s family and friends, the brothers were sentenced to 17½ years in prison.

In court, the Ogoshis said they viewed their extortion operation merely as a small financial scam — to which Totten took strong exception.

“There was an utter disregard for human life,” Totten said. “They were just casually telling this victim that he should kill himself if he wasn’t going to pay.”

Locking up the Ogoshi brothers does little to stop the danger. Samson Ogoshi ominously wrote in a legal filing that “blackmail is prevalent in Lagos,” stating he knew of “hundreds of people [my] age … engaged in similar scams.”

It’s why Beccaccio notes that “arresting our way” out of the problem is not feasible.

Awareness, especially in the United States among potential victims, is the only solution, she and others said.

TIME MOVES ON in the Upper Peninsula, although never quite the same. Jordan, gone in the middle of the night, will never return.

All that is left, way up here on top of the country, is to scream out warnings.

The DeMays and Jenn Buta contend that something like a serial killer is on the loose — international crime rings raiding American homes to blackmail, emotionally torture and then kill American boys — and that almost no one is noticing.

John DeMay and Lowell Larson have given presentations across the country — including high schools and law enforcement conferences. Buta operates social media accounts to raise awareness to teens and their parents, all while trying to raise younger two daughters of her own. They answer messages. They lobby politicians.

John and Jessica DeMay never spent another night in the house where Jordan died. John, who works in real estate, cleaned and fixed it up (even personally patching the bullet hole in the drywall of Jordan’s bedroom) before selling the place.

Still, the reminders of Jordan are constant and crushing.

In the good weather they like to sit on their boat — DeMayflower — in Marquette’s Lower Harbor, next to an old ore dock that once made this town an industrial power and now serves as a hauntingly beautiful testament to the region.

Yet that’s also where Jordan, as a middle schooler, loved to jump and spin into Lake Superior. John, meanwhile, thinks about Jordan’s recently passed 21st birthday and how they might have celebrated with a day of fishing before hitting a downtown bar for a legal beer, an always powerful father-son relationship morphing into an adult friendship.

Mostly they wonder what Jordan could have become, what Jordan would have become.

“He was going to tackle the world,” John said.

Kyla, meanwhile, will soon begin her senior year at Northern Michigan, trying to spread the word as well. In one of her classes, she made a presentation about the crime that uprooted her life.

“The first thing I asked the class was: ‘Has anyone heard of sextortion?'” Kyla said.

She was hopeful that her peers were familiar with it, that awareness was spreading, at least here in Marquette.

“Only one hand went up.”

If you are experiencing a mental health crisis or know someone who is, call or text 988, the national Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.